Lifting Her Voice

- Megan Griffin

- Feb 8, 2021

- 6 min read

The day my sixth-grade teacher Ms. Hartman—a stern, perfectly coiffed brunette with an array of glasses in every shade of the rainbow—announced that we would participate in a mock presidential debate, my little introverted heart froze. While eager to know more about what seemed to be a peculiar election year—there were three viable candidates: the incumbent George H.W. Bush, the rising star from Arkansas Bill Clinton, and the entrepreneurial Texan Ross Perot—the part of me fearful of both public speaking and disagreement of any kind died a little. I recall desperately hoping to be assigned Bush or Clinton because at the very least I had a vague, albeit naïve, inkling of what it meant to be a Republican or Democrat; despite our shared Texan roots, Perot and his Independent party might as well have been from another planet.

My nightmare, of course, was soon realized: Ms. Hartman assigned me Perot, with a specific focus on environmental policy. Perhaps sensing my desperation but perhaps also delighted to speak with their quiet middle daughter about something other than Anne of Green Gables, my parents became my research assistants: my mom and I drove to Perot’s local headquarters to pick up his campaign book United We Stand, and my dad and I scoured the local newspaper and the national morning news shows—Good Morning America with Charlie Gibson and Joan Lunden was the family favorite—keeping our eyes and ears open for any presidential campaign news.

Three relatively intense weeks later, armed with as much data as my eleven-year-old mind could hold, I conquered the seemingly impossible: I crushed that debate. To my surprise, it felt good to challenge my peers in such a civil way, and while I was certainly no budding policy wonk, I could communicate the basic tenets of Perot’s policy while contesting those of Bush and Clinton. Guided by Ms. Hartman’s faith in us, my classmates and I had modelled intellectual growth and learned a bit about empathy: we listened, we learned, and most importantly we celebrated each other’s successes. The debates, I realized during the post-debate class party, were not actually about winning but about practicing those skills necessary to becoming more mindful citizens.

Ms. Hartman’s spirit has followed me throughout my educational journey; what I would tell her today—had she not passed away from cancer shortly after I left her classroom—is that she gave me a glimpse of what it meant to have a voice: to have something to say, a (safe) space to say it in, and the confidence to believe that it mattered—to myself, to my teacher, to my peers. Now, as an English educator at an all-girls school, I see echoes of my sixth-grade self in many of the students I teach and advise: young women curious but still hesitant and perhaps ultimately overwhelmed by anything that seems remotely political.

As a moderator for Ignite, a non-partisan organization that develops political leadership in women, I am often reminded of one reason why so few women run for office: self-doubt. Doubt that they know enough about public policy, doubt that they are qualified, doubt that they are not prepared. Men, however, often do not suffer from this lack of confidence, recognizing that what they do not know, they can learn along the way. But if we are going to build and sustain a healthy democracy, we need to cultivate young men and young women who are comfortable in the “not-knowing”—comfortable because they have the skills to find the answers they need—and who are motivated not by winning but by a desire to understand.

In the weeks following the February 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, I was glued to my screen as I watched as dozens of students passionately spoke about the need for gun control reform. I kept asking myself: “Who are these young people? And more importantly, what are they doing in their classroom that has so clearly prepared them to speak?” I immediately headed to their high school’s English Department webpage where I saw a junior-level curriculum rich with non-fiction texts on the American experience and a series of assignments that asked students not just to analyze these texts in some academically distant way but also to interrogate their own personal understanding: why do I believe what I believe, how might I challenge my initial perceptions, where might compromise be possible? It was clear: my own junior curriculum needed a civic-minded facelift. Channeling the energy of Ms. Hartman and these young students, I embarked upon a curriculum journey that I now refer to as the Citizen Rhetor Project. In short, I define the term “citizen rhetor” as a socially aware writer and speaker who not only has the confidence to engage in written and oral conversations about public issues but also the empathy to do so in a way that seeks both to understand and to eventually act.

Rather than overhauling my entire curriculum, though, I started by rethinking my research unit, which had traditionally been one that considered The Great Gatsby or another canonical novel within its historical context. Some of the questions that framed my initial thinking included: How can writing encourage the confidence of girl writers through developing their voices, giving them permission to engage in the public conversation? How does the act of writing and research draw out the spoken voice? What does a writing and research curriculum look like when we place students’ development of their writer identity at the center of their civic identity?

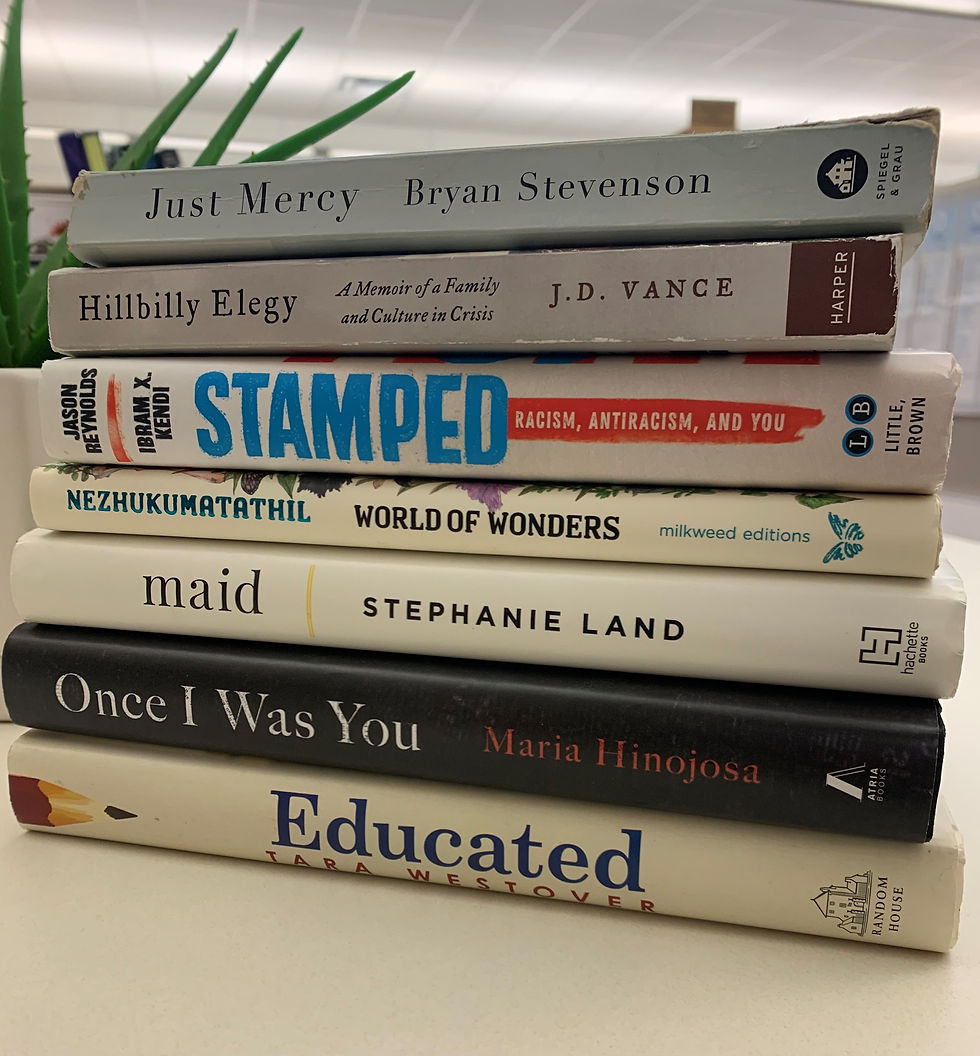

While this unit has taken on various manifestations in the past few years, with the help of my innovative colleagues, it exists in this current form: Students begin by reflecting on their own interests in the American public conversation—environmentalism, social class, race, gender, immigration, and education. These interests then lead them to select one of the following texts for a book club read: Tara Westover’s Educated, Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped, Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy, Maria Hinojosa’s Once I Was You, Stephanie Land’s Maid, J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, and Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s World of Wonders. Except for Stamped—although even that text integrates a personal element into its retelling of history—all of these are memoirs that explicitly confront contemporary concerns, articulating how the authors’ lives have been shaped by larger forces: racism, economic stagnation, climate change, etc. Ultimately, each offers a sense of realistic optimism for how we might move forward, especially in ways that recognize the humanity of those affected. In an interview with Ezra Klein following the publication of Hillbilly Elegy, author J.D. Vance reinforces this point: that until policymakers understand the complex lives of the people they serve, then any policy, no matter how well meaning, will come up short.

Throughout the Citizen Rhetor research process, students negotiate potential conflict, practice empathy, and learn to be confident in advocating for their position. Having my students read memoirs as their entrance into the research provided the link that had been missing when I launched this unit. As they develop their questions and build their annotated bibliography, this human connection is at the heart of their research, a connection they supplement later in the process with a personal interview. Too often we approach research from a place of separation, of distance: using language that, intentionally or not, can dehumanize our subjects. Students—young women especially but also of course young men—love personal stories. Storytelling, as Jonathan Gottschall so thoroughly captures in The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, is innately wired into us, and drawing upon research in neuroscience and evolutionary biology, he reinforces just how consciously and unconsciously the stories of others change us. From the beginning of their research process, then, my students are motivated, I hope, by a desire to understand someone who might be very different from them:

Building confidence and empathy are two key parts of a curriculum that places student wellness at its core; along with this confidence and empathy, I also hope this project fosters a sense of purpose, perhaps even that Aristotelian concept of eudaemonia: eu (good) and daimon (spirit). A purpose-filled life is one that is not harried, anxious, or persistently uncertain. It is also not one rooted in a superficial experience of happiness but rather in the development of a sustainable life that cultivates trust in our own agency, even in the face of a seemingly chaotic world beset by a pandemic and marked by both peaceful protests and violent insurrections. In writing, reading, and learning from each other, my students are developing this “good spirit,” knowing that they can engage in productive, political conversations where the outcome is awareness and understanding.

Looking back on that 1992 election year, I do not know that I fully agreed with Perot’s policies, but trying them on for a few weeks set me on a path to better understand what I did believe, and for that I can only simply say: Thank you, Ms. Hartman.

Dr. Megan Griffin is a Found Poet Who Finds Herself Poetically Searching.

"Lifting Her Voice" is part of our February series on empathy and teaching writing.

Sources:

Gottschall, Jonathan. The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human. Mariner, 2012.

Ignite, Ignite National, 29 Jan. 2021, www.ignitenational.org.

Klein, Ezra. “A Conversation with J.D. Vance, the Reluctant Interpreter of Trumpism.” 2 Feb. 2017.

Comments