The Flow State and Mindful Writing

- Kate Schenck

- Feb 15, 2021

- 7 min read

In December 2019, I had a major panic episode that launched me from a robust and busy life of performance, achievement, and purpose into the small, tiny existence of life lived by the hour and filled with fear. After undergoing two MRIs, a spinal tap, brain wave testing, and blood work with two neurologists, I learned that I was healthy, and the tingling and numbness in my arms and legs went unexplained. My internist, who was coaching me through this extensive testing process, ultimately diagnosed me with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, which manifests primarily through health anxiety and in my case, bodily sensations such as the tingling and numbness. By the time I learned this diagnosis, it was early March 2020 and within weeks we learned that school would be transitioning online because of the COVID pandemic. I began my personal journey to understand and manage my anxiety at the same time humanity was grappling with a worldwide health crisis, which forced me inward and into my study of PTSD, trauma, recovery, and our bodies.

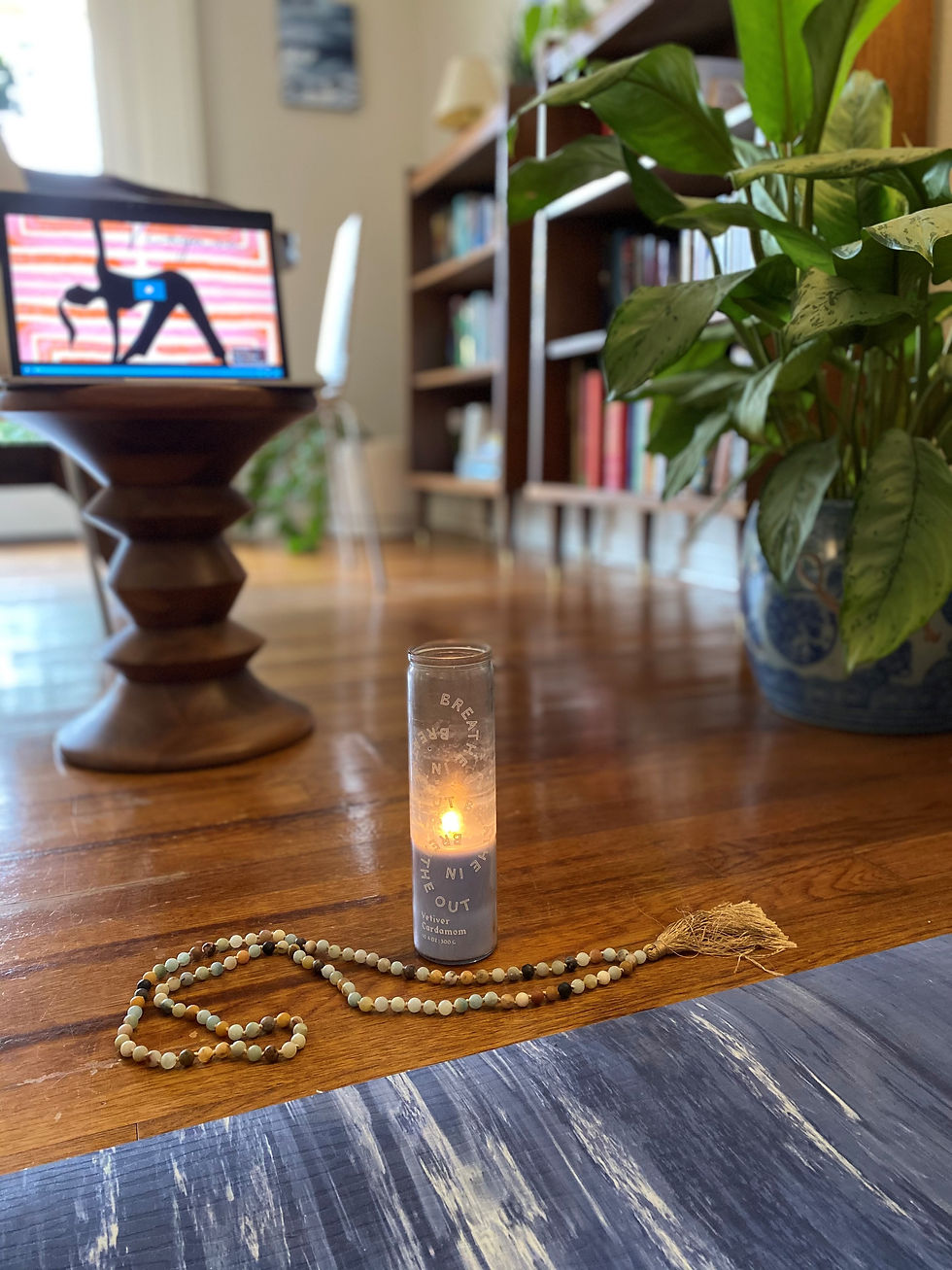

As a lifelong learner, my instinct when I feel lost is to study and learn how I can make changes to navigate and survive the wilderness of my spirit. My yoga practice at home has become my lifeline to healing. When I am on my yoga mat, I move my body, focus on breathing, drink water, and remind myself that my body is strong and can do hard things. These activities all seem basic, but teaching during a pandemic, while also learning how to manage health anxiety, has taught me to take one day at a time, and appreciate that the care we give ourselves does not have to be epic in scale to be significant; it rests in every small action we take to stay healthy. In The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk states, “Traumatized people need to learn that they can tolerate their sensations, befriend their inner experiences, and cultivate new action patterns.”

I am naturally drawn to all mentions of the heart in my yoga practice. When my instructors call a pose a heart opener or say that a pose is accessing the heart chakra, I pay special attention and feel like I am tapping into some part of me that is longing or struggling. When I am “in the grip” of an anxious episode (to quote my wonderful therapist), my heart feels tight and restricted, which can manifest physically through heart palpitations and shallow breathing. Like so many others, I believe I carry much of my anxiety in my heart muscle, so I often struggle to consider opening my heart, especially when it feels heavy and worried.

Another method I study to help me open my heart and develop self-compassion is mindfulness and meditation. Over the past several years I have listened to mindfulness teachers such as Tara Brach and I have learned that mindfulness, or stepping out of my egoic thoughts and into the present moment, helps me break free of the grip of my anxiety, as well as calm my nervous system. Meditation is difficult for me, but I intuit that, along with physical exercise, meditation is part of my healing process and is helping me manage my thinking and signal to my physical body that I am safe.

As with most things in my life, I naturally began thinking about how my personal experiences with anxiety, yoga, and mindfulness relate to my teaching and my students, who are always on my mind. I don’t remember how I learned about the Mindful Schools organization, but my love affair for their professional development began when I took their Mindfulness Fundamentals course and continued through their course on Difficult Emotions. The Mindful Schools program provides support and guidance for teachers who want to practice mindfulness personally to ultimately use their practice in their classrooms to benefit their students. They also reinforce that mindful teachers create calm and heartful teaching spaces, and that caring for teachers is related to caring for students, which is a message I love. Currently, I am taking a course on Mindfulness in the Classroom and I know that at some point I need to shift from mindfulness student to mindfulness teacher if I am going to bring the beauty and the stillness of mindfulness to my classroom, but I have been hesitant and nervous to do so.

Last week, I decided to jump in feet first and lead my first meditation to begin class. We were having a vocabulary writing quiz that day and as the girls entered the classroom, our space became a hive of pre-quiz jitters -- the low hum of chatting punctuated with higher pitched buzzing of the anxious “stress Olympics” of teenage girls. I felt imposter syndrome as well as worry that some of my students would be disengaged, or worse, uncomfortable if I attempted a brief meditation to begin class. I have always attended meditations, not led them, but I am very aware that to understand the risk-taking I ask my students to do in our writing process, I need to take my own risks as well.

As I have learned over the past year or so, worry and anxiety come from thoughts about the future. I once heard author Dave Mochel speak and he gave a perfect explanation: faith is not knowing what will happen but believing you have the tools to handle it, while anxiety is knowing what is going to happen next, while believing you do not have the tools to handle it. The opposite of a worried, anxious mind is a present mind, and as a teacher of chronic worriers, I have been wondering how training our minds to be more present will have benefits, not only for students personally but also for their writing.

As a yoga student and creative person, I am very interested in what is called “a flow state,” or time in which we step out of our overthinking brains and into the present moment, focused completely on our breathing, movement, and/or the task at hand. According to psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in his book titled Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, “the optimal state of inner experience is one in which there is order in consciousness. This happens when psychic energy—or attention—is invested in realistic goals…the pursuit of a goal brings order in awareness because a person must concentrate attention on the task and momentarily forget everything else.” When I am in a flow state, I am relaxed, open, and fully concentrated on what I am doing, achieving a peace that allows me to open my heart, speak my truth, and feel fully alive.

My goal in beginning class with a meditation was to help my students settle their nervous systems, focus on their breathing, and clear their minds of any anxious clutter, helping them get into their flow state. As I was leading them in breathing exercises that began with asking them to say their own name (in their minds) followed by the word “relax”, they were visibly enjoying the experience, so much so that, when given the option to begin journaling or continue the meditation, almost all of them remained in their meditative posture with their eyes closed. The next day in class, several students asked if we could open class with a meditation. Even if they just wanted a few minutes to sit and be with their breathing, close their eyes, and hit the pause button on their packed daily schedule, this feels like enough.

My current meditation is how achieving the flow state through mindfulness can be beneficial to students’ writing practice. After attending the Bard Institute for Writing and Thinking and reading the work of Peter Elbow on the benefits of incorporating free writing into the daily lesson, it occurred to me that free writing is a flow state. In Writing Without Teachers, Elbow argues that writing for ten minutes, unedited and unrushed, allows you to break the habit of “compulsive, premature editing” which “doesn’t just make writing hard, it makes writing dead. Your voice is damped out by all the interruptions, changes and hesitations between the consciousness and the page.” English teachers spend so much time trying to teach voice in writing, when each student already has a voice— it just needs a space to exist by breaking free of the self-consciousness and insecurities that often come from feedback.

Through achieving a flow state, we control our consciousness and bend it towards positive acceptance versus self-criticism, improving our writing fluency along the way. And through a more empowered consciousness we are open to growth and to receiving, versus rejecting, writing feedback. In “The Feedback Fallacy” published by the Harvard Business Review, writers Ashley Goodall and Marcus Buckingham argue that, “We’re often told that the key to learning is to get out of our comfort zones, but these findings contradict that particular chestnut: Take us very far out of our comfort zones, and our brains stop paying attention to anything other than surviving the experience. It’s clear that we learn most in our comfort zones, because that’s where our neural pathways are most concentrated. It’s where we’re most open to possibility, most creative, insightful, and productive. That’s where feedback must meet us—in our moments of flow.”

I am not sure where this journey will lead, but I love the challenge of modeling this uncertainty and curiosity for my students. I am exploring how to create mindful writing prompts and practices in my classroom to help my students unlock their anxious hearts and achieve a flow state, which will create the space for them to (hopefully) learn to love writing and to develop their empathy, self-compassion, and voice through the writing process. If writing can be a mindful exercise, then the benefits can ripple out beyond our classroom and into my students’ lives as they navigate not only being a teenager, but being a teenager amidst a global pandemic.

“The Flow State and Mindful Writing” is part of our February series of reflections on English teaching and developing empathy.

Kate Schenck is a collector of pigments and spices, dreamer, and builder of tables for lesser heard voices.

Click here for more information on the Mindful Schools program.

Sources:

Buckingham, Marcus and Ashley Goodall. "The Feedback Fallacy." Harvard Business Review. March-April 2019.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial, 1990.

Elbow, Peter. Writing Without Teachers. Oxford University Press, 1973.

Van Der Kolk, M.D., Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking, 2014.

Sometimes one need to be forced, for example, not to think more than 10 seconds, and just keep typing away, like this tool doing flow-writing.com